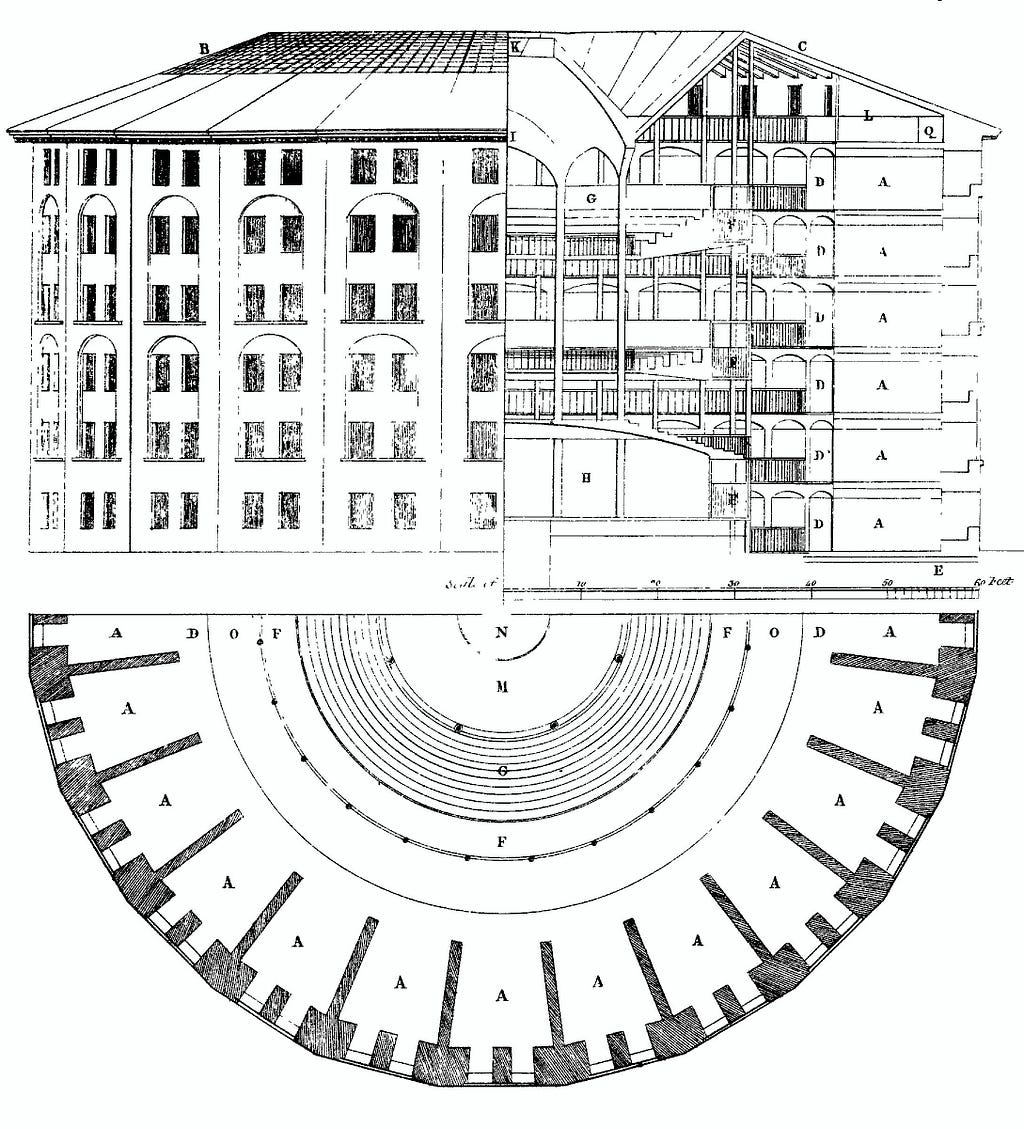

Let me start with one of my favorite visualizations of surveillance (not my original idea). In the late 18th century, an English philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, designed a brutally efficient prison architecture. The main innovation is quite simple: prison cells are arranged in a circular format surrounding a central watchtower. The watchtower theoretically only needs to be manned by one person, who is obscured from view from the inmates. At any given moment in time, the watchman can observe any prison cell, while the inmates cannot see which way the watchman is looking.

It’s mercilessly effective. Without needing to hire a guard to watch every individual inmate, or even punish every instance of bad behavior, the prison is able to exert control over everyone. With the knowledge and fear that they can be monitored at any given moment, the prisoners must behave under the assumption that they are being monitored at every moment.

Here, I will try to design a digital panopticon to offer the same level of oppression, built for the modern-day electronic lifestyle. Note: this article is merely a hypothetical thinking exercise to create a fictional dystopia, not a conspiracy theory.

Step 1: The Walls

“Arguing that you don’t care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say.”

― Edward Snowden

The first step is to build my digital prison building, then convince my population to live in it. This step is surprisingly easy to build: I weave hardware sensors and software data collectors into everyday objects. I market my products as “smart” so people will trust them enough to bring them into their homes, package some with shiny electronic jewels so people will wear them, and offer my online services in exchange for the permission to collect all data — I call those services “free.” I’m not lying, initially: their data isn’t worth anything just like having a window in my home isn’t an invasion of privacy if nobody is looking through it. But I now have billions of windows, ranging from helpful smart thermostats to life-saving heartbeat monitors, in every person’s home.

Step 2: A Central Watchtower

“I fear the Greeks, even when they bring gifts.”

– Virgil

The second step may happen concurrently: build my watchtower. This part, of course, requires some disclosure to the new residents of my homely prison. I simply demonstrate that I’m able to respond to their behavior — good, bad, or otherwise — to let them know I’m watching. Here is where I do better than Bentham: I actually can watch everyone at the same time without hiring billions of guards.

In CS188 (the introductory artificial intelligence course at UC Berkeley), a student with a year’s programming experience can learn to write a machine learning model that classifies handwritten numbers correctly with less than 20 lines of code (and a few imported libraries). Here are a few examples these students can put together in a two-day hackathon or summer intern project: collect birthdays and remind everyone to make each other happy on their special days. Tweak the spellcheck to learn slang after a user corrects it enough times. Classify videos using user-inputted genres or keywords to make smart recommendations to viewers. Seems innocent enough.

Step 3: Locking the Doors

“The user’s going to pick dancing pigs over security every time.”

– Bruce Schneier

The key to our third step is to convince our residents that they want to live here forever, while we continue to build more cells and more walls until there is nowhere else to live.

Whatever the situation, I know the exact movie, game, or trinket to sell my prisoners to make them happy. When they search for the news, I know what they want to see and give them the laws to be angry about and politicians to hate. I know the best romantic restaurants, flower arrangements, and perfume boxes. And when I notice breakup tunes and ice cream cartons, I know which romcoms to recommend. I am their best friend.

I’m even able to promise to cure cancer: the data I collected turns out to be worth trillions of dollars as profiles comprised of genetics, symptoms, diagnoses or misdiagnoses, medicines and side effects are used to compute individualized treatment plans. This is an absolute win for patients and health insurance companies alike, but the people whom I collected data from didn’t receive a penny. I tell them it doesn’t matter: they couldn’t have done much with just their personal medical record anyway.

Step 4: The Chains

“It is impossible to correct abuses unless we know that they’re going on.”

― Julian Assange

Up until this point, none of our prisoners feel that their rights have been violated. In fact, it’s easily argued that life quality has increased. Let me show you how I can abuse them while maintaining this benevolent illusion. I introduce real-time price adjustments for my consumers: everybody took economics in high school and understands that by following supply and demand principles, they get the best price. I also offer an intuitive reputation system: a star rating for each consumer and merchant to transparently determine the prices they can demand. I’m giving them more power!

Alice: Based on Alice’s social media posts and messaging history, I happen to know she has a grandma living in Japan who is suffering from a cardiac disease. I know Alice’s discretionary income to the dollar because she posted where she works and I have been monitoring her spending habits, so I double the price of plane tickets to Japan for her. I know she’ll pay it. I recommend some smoothie recipes for heart health and use the correct marketing words to sell her ingredients and homeopathic medicine.

Bob: Across the country is Bob, a student who has decided to become a ride-sharing driver to help pay his bills. Unfortunately, he has a rough start: his unfamiliarity with the app causes him to miss a few stops, so he gets bogged down with low star ratings. He tries to recuperate but keeps getting matched with riders who also have low star ratings; the scores they give each other carry less weight because they are deemed less “trustworthy.” Months go by and Bob manages to get up to a respectable 4.1, but one mistake with a five star-rated rider bumps him back down to where he started. Bob suffers financially because his poor reputation gets fewer rides and lower rates.

Charlie: Later, Alice and Bob get married and have a child named Charlie. I can make an educated guess on the baby’s ethnicity and socioeconomic status based on his parents’ geographic location, interests, and shopping history. Thus, this baby already has a profile before he is even able to use a cellphone. My machine learning models learn all of society’s gender, racial, and socioeconomic biases. Charlie and his parents will receive targeted advertisements nudging him into the lifestyle he is stereotyped to belong to. He might never have the chance to explore educational opportunities or higher-income career paths. Hey, I’m not racist — it’s just correlations in the data.

Step 5: Hope

“Working in porn is awesome, until you want to find another job.”

― anonymous person who used to work in porn

I read somewhere that if you have a chicken factory with an open back door to a 10×10 ft plot of grass, you can call the chickens “free range chickens” (please don’t quote me on this). I need to give my prisoners a bit of hope, so I start a company that allows people to game the system a little bit. The company exploits real workers to run various accounts, visiting certain key websites to generate an online profile — just like a farmed video game account. The basic profiles are quite simple: “wealthy white female” and “middle-class millennial,” but I also sell older profiles that have been trained to include “Ph.D in neuroscience,” “loyal customer of this specialty store,” and “hardworking low-income student interested in becoming a doctor.” The rich can afford to be anybody they want; my service becomes very popular for college applications. Those who don’t have this option, however, have to control every scroll and click as they move through their digital life.

Why Privacy is a Human Right

“Security is always excessive until it’s not enough.”

– Robbie Sinclair

While the inhabitants of my fictional digital panopticon enjoy technological solutions to improve everything from entertainment to healthcare, their behaviors and lives are slaves to what their data says about them. No doubt we all understand the value of lots of data fed into well-engineered models, but we must also establish that an individual’s data is worth something too. And hopefully the mere option of privacy was shown to be insufficient; privacy should be the default.

My fictional prisoners are unable to retake control of their own data because they were misinformed in the initial stages and allowed to the doors to lock before they knew what they were getting themselves into. It is not the users’ responsibility to understand which security implementations they want; the right to privacy must be respected and protected by the empowered. However, as we consumers begin to discover the implications of exciting new technologies, we mustn’t be tricked into giving up our most basic rights for bells and whistles.

Works Referenced and Stuff To Check Out

Assange, Julian. Cypherpunks: Freedom and Future of the Internet.

Galloway, Alexander R. Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralization.

Hughes, Eric. A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto.

“Nosedive.” Black Mirror, season 3, episode 1. Netflix.

xoJane. “Working In Porn Is Awesome, Until You Want To Find Another Job.” HuffPost, HuffPost.

About Gloria

Gloria Zhao is President of Blockchain at Berkeley and a UC Berkeley student majoring in Computer Science and Psychology. She also teaches Blockchain Fundamentals, an undergraduate Berkeley EECS course.

Digital Panopticon: Why Privacy is a Human Right was originally published in Blockchain at Berkeley on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply